The Green Party policy is to impose a new wealth tax as its main plank to fund a proposed revamp of the income support system. It’s an interesting proposal, but unlikely to be widely debated, let alone implemented. While many countries have some form of capital gains tax (CGT) to tax capital, very few countries currently impose a general wealth tax.

Prime Minister Ardern promised a year ago not to impose a CGT while she remained in office. Labour could potentially look at some form of wealth tax. However, the Tax Working Group (TWG) in 2019 specifically rejected a wealth tax as “a complex form of taxation that is likely to reduce the integrity of the tax system” and it would seem difficult to see how it could now be resurrected (at least in the form the Greens propose).

The Greens wealth tax policy is a tax of 1% on the annual value of an individual’s assets (net of debt) over $1m and 2% over $2m. There will be a $1m tax-free threshold. The value of assets held jointly could rightly be split between the joint owners. To illustrate the amount of tax that would be payable for an individual:

| Net wealth | Wealth tax |

| $1m | 0 |

| $2m | $10,000 |

| $3m | $30,000 |

| $5m | $70,000 |

All assets would be counted- family home, farms, shares, real estate, KiwiSaver, beach houses, business assets. Excluded, in addition to the first $1m asset value, would be any household assets (including chattels and vehicles) valued at less than $50,000. If you have not got the cash to pay the tax, there will be an option to defer (supposedly at an interest cost). Trust assets would be punitively taxed at 2% (with no $1m tax-free threshold) to the extent the assets cannot clearly be linked to a particular beneficiary.

A wealth tax is similar to a CGT in that they both seek to tax capital rather than income from capital or from labour. CGT usually taxes only the gain once the asset is divested, whereas the wealth tax is an annual tax on the value of the asset itself. The CGT outlined by the TWG in 2019 proposed a tax on realised gains from assets, with an exclusion for the family home.

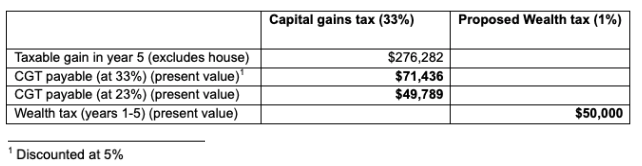

While 1% and 2% wealth tax rates are touted as modest, the tax is imposed on the asset value rather than any capital gains from the asset. Would a person be better or worse off than under a CGT? To illustrate, assume a person owning $2m total net wealth- $700,000 in a rental property, a small business worth $300,000 and a $1m family house. Assuming asset values increase by 5% pa and all the assets are sold in the 5th year. The respective wealth tax (over 5 years) on the $1m of assessable net wealth, or CGT in year 5, would be:

In this example, the wealth tax is equivalent to a CGT imposed at 23% rate. However, if the person started with net wealth of $3m (taxed mainly at 2% wealth tax rate), that is equivalent to a 39.5% CGT! If the Prime Minister rejected the proposed CGT, she must surely not even entertain this proposal.

To many, taxing some or all of the value of the family home will be abhorrent, although not taxing the first $1m asset value will exclude many family homeowners. Those on a modest income with most wealth tied up with a valuable mortgage-free house and KiwiSaver may not consider themselves particularly wealthy. Those owning a closely held business may argue it punitive to further tax the benefits of years of risk-taking and hard work. Farm owners struggling with seasonal challenges or depressed commodity pricing will be equally unsupportive of the proposal.

The Green Party estimates the tax would raise $7.9b in the first year, which is not a minor amount (in comparison, total PAYE and corporate tax raise $33b and $15b respectively).

The TWG recommended a broader CGT and rejected a wealth tax. Only five major countries imposed some form of net wealth tax in 2017 (Argentina, France, Norway, Spain and Switzerland) and many are making steps towards removing it. Some of the issues why wealth taxes are shunned in most countries, are:

- They create an incentive for citizens to migrate offshore.

- Potential to discourage business investment and risk-taking

- Difficult annual valuation issues

- Issues for major investors in cash-strapped start-ups or other businesses

- High levels of avoidance and evasion

- Difficult and costly to comply with and administer

- Double tax where company tax is paid on earnings that also add to a shareholder’s wealth, even if retained.

- Written by: TPTS

- Posted on: June 30, 2020

- Tags: TPTS, TPTSNZ, Transfer pricing NZ, WealthTaxNZ, WeathTax