A gigantic shake up is imminent for the international taxation of many multinational groups that use the ‘digital economy’ or are simply selling branded consumer goods. These international tax changes will impact a wide range of companies doing business in New Zealand and some New Zealand companies marketing their products/services offshore.

While most thought that the BEPS related international tax changes were done and dusted with implementation of OECD’s 15-Action plan, there was never consensus for a course of action regarding the taxation of the digital economy (Action 1). The OECD subsequently commenced a programme to work towards a consensus solution to ensure that companies That work programme is split into two “pillars”- Pillar One addresses the international taxing rights, allocation of profits and potential nexus rule and Pillar Two is to ensure companies pay a minimum level of tax. Public consultation papers have now been released under for each pillar.

We first look at OECD’s “Unified Approach”1, which is a proposed solution under Pillar One.

Companies conducting social media businesses, search engines, streaming services, online advertising and online retailers are obvious targets for this new approach. A feature of many business models is that they can typically exploit a country’s market without having significant physical or personnel presence.

But the Unified proposal targets a broader group than just digitised businesses. It aims to apply to any large ‘consumer facing’ business group that generates revenue from supplying consumer products or providing digital services that have a consumer facing element.

Consumers being individuals who buy for personal purposes and includes users. The exact scope has yet to be determined. It is not entirely clear whether the approach is confined to

B2C transactions but could readily include B2B where the Group does not market its products directly to consumers but sells through intermediaries, which is the case for most branded goods. Certain businesses are likely to be carved out- specific mention was made of the extractive and commodity industries and possibly financial services.

Consumer facing multinationals will be deemed to have a ‘virtual tax presence’ in a country simply by virtue of selling goods or services in that country (including through a related or non-related distributor). That is additional to any subsidiary or traditional permanent establishment (branch) the Group may already have in that country from which it earns revenue. The proposal extends the traditional international tax rules that have been in place since the 1920s.

The way it will work is that where a group company in one country owns marketing intangibles (e.g. brand, data, customers, users), it may be required to allocate some of its residual profits earned from those marketing intangibles to other countries where the consumers are based . The residual profits will be calculated by excluding from group profits certain profits that are deemed attributable to routine functions. Residual profits attributable to trade intangibles (like algorithms, software, technology), capital or risk are not intended to be subject to allocation; only the profits from ‘marketing intangibles’. If there are residual losses, these would also be allocated. A de minimis level of country sales will likely be set before any such allocation is required to be made to a particular market country (that level may be calibrated to account for countries with smaller markets).

It is further intended that the country undertaking the marketing and sales activity, such as through a local related distributor, will be entitled to a given baseline fixed return for those functions.

Countries such as Ireland and Singapore, where some multinationals have located regional marketing hubs and where significant profits have accumulated, are likely to be losers in this change. Large markets, such as India, US, China and larger European countries may be the winners. Multinationals forced to allocate some intangibles’ related profits from low tax countries to higher taxing market countries, will suffer an increased effective tax rate. New Zealand could well be a net beneficiary given that many large foreign multinational in- scope groups market their products to New Zealand consumers. But this will depend on the de minimis revenue threshold set for particular market countries and what return New Zealand distributors could expect to report for baseline sales and marketing efforts.

A suggested de minimis would seek to include in this new regime only Groups with substantial revenue. A possible €750m revenue threshold has been mentioned which, at that level, would exclude many New Zealand headquartered companies. It remains to be seen the extent this new approach could have implications for a Group such as Fonterra which would exceed the revenue threshold and markets and sells its branded products offshore.

The OECD provide one brief illustration of how this regime would work- X Group provides global streaming services and ParentCo (in Country 1) holds all the intangibles for that business and earns most group profit. Its subsidiary (Subco) in country 2 markets and distributes all the services and sells to consumers in country 2 and remotely into country 3, where it has no traditional tax presence. If the sales in countries 2 and 3 exceed a specific threshold, then a portion of the residual group profits in ParentCo would be liable to be taxed in each of countries 2 and 3. In addition Subco is taxed in country 2 on some fixed return for its marketing and distribution activities (which return could still be disputed by a tax authority or Subco as not representing its baseline functions).

Some critics argue that the Unified Approach is a clear departure from the BEPS reforms. While the BEPS Actions 8-10 sought to retain and improve the application of transfer pricing’s arm’s length principle, the Unified Approach is essentially introducing a formulary apportionment method for in-scope businesses and largely abandoning the concepts in Actions 8-10.

The Secretariat Proposal is not yet a consensus of the 134 participating countries in this project. It is intended to form the basis for countries to discuss and negotiate an agreed position before the end of 2020. As always, the devil is in the detail, which much of this Unified Approach has still to produce. Turning now to ‘Pillar Two’, which calls for the development of a co-ordinated set of rules to address ongoing risks from multinationals shifting profits to jurisdictions where they are subject to no or very low taxation. For example, US Groups locating intangibles in tax havens and developing regional marketing intangibles in countries such as Ireland and Singapore.

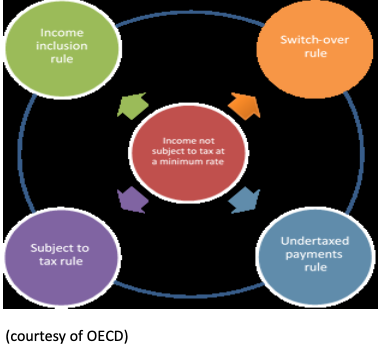

The aim is to create a disincentive for Groups to locate their activities in low tax countries and for countries to compete in a ’race to the bottom’ on corporate tax rate. OECD has also now released a public consultation document on Pillar Two which proposes a new regime for global anti-base erosion (or ‘GloBE’). This document proposes a radical change to the international tax architecture to ensure that the profits of international operating businesses are subject to a minimum rate of tax. The proposal seeks a set of rules applying through domestic law or tax treaties to all countries. The proposal involves four component parts which is encapsulated in the diagram below. Unfortunately, the proposal has not been developed into any specific proposal and at this stage is mainly raising questions for consultation than presenting a specific regime.

For New Zealand headquartered companies, few would likely operate or have substantive profits in countries with genuine low or no tax rates. The New Zealand CFC rules already attract most forms of passive income but would not typically catch genuine sales being made through a low tax jurisdiction. Certainly, the general anti-avoidance rules and the revised transfer pricing rules in New Zealand would act as a disincentive for New Zealand companies to try and relocate profit making assets in a jurisdiction where there was little substance.

The most important feature of the GloBE proposal is an ‘income inclusion rule’, whereby income of a foreign branch or a controlled subsidiary could be further taxed if that income was subject to tax at an effective rate that is below a minimum rate. Essentially this would likely operate like a broad controlled foreign company regime, with aggregation of subsidiary profits at head office level and a possible ‘top-up tax’ payable. Consideration is being given to the possibility of doing these calculations using profits as per IFRS accounts rather than performing country specific tax calculations.

The proposal suggests that there will be rules around the ‘blending’ of profits from different sources and from both low and high taxing countries. Various carve-outs are likely and de minimis thresholds are to be considered. For example, carve-outs could apply to jurisdictions already meeting certain minimum BEPS related criteria, for returns on tangible assets or to exclude subsidiaries with related party transactions below a certain level.

Other suggested rules are:

An ‘undertaxed payments rule’ – which would deny a deduction or impose source-based taxation (including withholding tax) for a payment to a related party if that payment was not subject to tax at or above a minimum rate;

A ‘switch-over rule’ to be introduced into tax treaties – would permit a residence jurisdiction to switch from an exemption to a credit method profits attributable to a permanent establishment (PE) or derived from immovable property (which is not part of a PE) are subject to an effective rate below the minimum rate; and A ‘subject to tax’ rule – would complement the undertaxed payment rule by subjecting a payment to withholding or other taxes at source and adjusting eligibility for treaty benefits on certain items of income where the payment is not subject to tax at a minimum rate.

The OECD call for comments on many questions posed as to the detailed make-up of this GloBE proposal by 12 December. We will provide updates as these important projects progress.

Footnotes:

1. OECD: A public consultative document; Secretariat Proposal for a “Unified Approach” under Pillar One

2. The allocation key is likely to be based on relative sales in each marketing country

3. For example, refer to Eden and Treidler; Bloomberg Tax; INSIGHT: Taxing the Digital Economy—Pillar One Is Not BEPS 2 (Part II)

4. OECD: Public consultative document; Global Anti-base Erosion Proposal (“GloBE”)- Pillar Two.

Our other insights can be found here: https://www.tpts.co.nz/blog/

- Written by: TPTS

- Posted on: November 19, 2019

- Tags: International Tax Changes, OECD

2 comments

Update on BEPS 2.0 – Transfer Pricing & Tax Solutions

March 6, 2020 at 10:07 am[…] and ‘Pillar 2’ initiatives (together referred to as BEPS 2.0) would work (see Nov 2019 article). Subsequently, OECD/G20 has provided an update of the project (OECD Statement) and OECD recently […]

‘BEPS 2.0’ will not be a windfall for New Zealand – Transfer Pricing & Tax Solutions

March 6, 2020 at 10:22 am[…] ‘Pillar 2’ initiatives (also together referred to as BEPS 2.0) would work (see our 11/2019 article and our […]